DAY-6: MILITARY – HEROES WALK AMONG US

Heroism is a quality that most people ascribe to people who respond extraordinarily in the face of imminent danger. They seem to do the opposite of what most people do. They run towards the risk and not away from it, hoping to help or prevent harm. Based upon this description, Black people living in America, particularly, young men hit the mark. Each day Black people leave their homes on their way to work or school in fear of losing their lives directly or indirectly due to racism.

I witnessed first-hand my father belittled by a white state trooper because he disagreed with him. With the threat of being arrested in front of his son, my father chose to fight another day. This form of heroism gets lost because it does not make the news. But here I stand, memorializing my father’s wisdom, who happened to be an armed forces veteran.

During the four-hundred years of chattel slavery, and directly afterward, our country participated in several wars. Some can argue either for or against our involvement, but there was one thing that I’ve always found very intriguing–Black people’s participation. Throughout the years, Black people have fought to secure their freedom, as well as the freedom of our country. This kind of audacity takes a great deal of unselfishness and vision. Despite the treatment that Black people endured, they bought into the tenets of the foundational documents that many in America aspired to live by.

African Americans developed a respect for freedom based upon how hard they were fighting for it and recognized it as a fundamental human right for ALL men. Even while enslaved, many laid down their lives fighting for a cause that was eluding them. As time moved forward and Black people received their freedom from active slavery, they still had to fight through racist views and mistreatment to participate. Yet they did and did it with dignity and a resolve to move towards the risk, not away from it.

Click on link below to view history of African Americans buried in Arlington National Cemetery

African-American History at Arlington National Cemetery

Over sixteen-thousand Civil War soldiers are buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Among these are many U.S. Colored Troops (the U.S. government designation for African-Americans who served in segregated U.S. Army regiments during the war) buried in sections 27 and 23. Their headstones are marked with the Civil War shield and the letters U.S.C.T. Three of these men are Medal of Honor recipients. Read More.

“BLACK PATRIOTS Of The Revolutionary War”

Listen As Kareem Abdul Jabaar elaborates on the impact of Black Patriots

Watch Full Video of The Black Patriots of the Revolutionary War

We have chosen to honor a select few groups and individuals who fought for freedom for themselves and for this great country. Let us honor their service to others and to America regardless of how America treated them. We must not let their service be forgotten or let those that died fighting for the ideals of our country die in vain. #LET THE TRUTH BE TOLD.

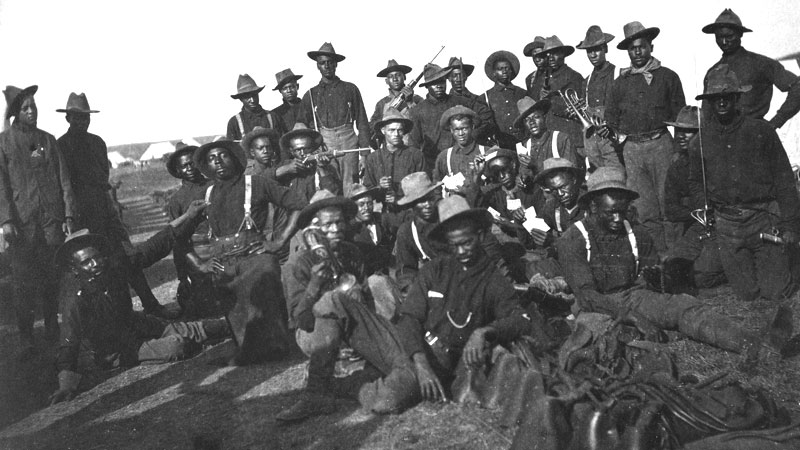

“BUFFALO SOLDIERS

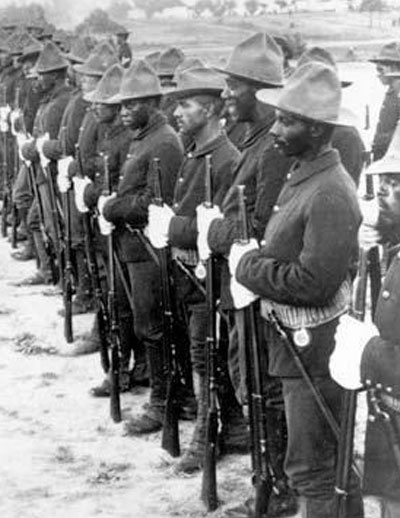

Buffalo soldiers were African American soldiers who mainly served on the Western frontier following the American Civil War. In 1866, six all-Black cavalry and infantry regiments were created after Congress passed the Army Organization Act. Their main tasks were to help control the Native Americans of the Plains, capture cattle rustlers and thieves and protect settlers, stagecoaches, wagon trains and railroad crews along the Western front.

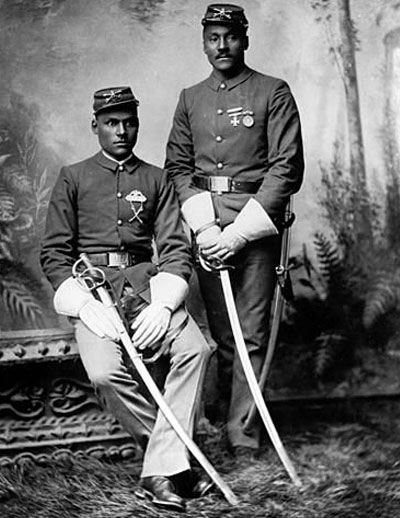

Buffalo Soldiers Officers

Buffalo Soldier In Formation

Spanish American War

George Henry Wanton was born on May 15, 1866 at Paterson, Passaic County, New Jersey. The son of William H. Wanton and Margaret (Miller) Wanton. George Wanton attended public schools in Paterson before enlisting in the U.S. Navy in 1884. Wanton served a four year enlistment and was discharged in 1888.

In 1889 Wanton enlisted at Paterson, in Troop M, 10th U.S. Cavalry. In 1892 Wanton received a promotion to Corporal but had been demoted back to his rank as Private when he earned the Medal of Honor.

Private Dennis Bell

Private George Henry Wanton

Private Wanton earned the Medal of Honor on June 30, 1898, at Tayabacoa, Cuba. His citation reads as follows: Voluntarily went ashore in the face of the enemy and aided in the rescue of his wounded comrades; this after several previous attempts at rescue had been frustrated.

On June 30, 1898, units of the 10th Cavalry, aboard the U.S.S. Florida, attempted a landing at Tayabacoa on the east coast of Cuba to link up with up with Cuban insurgent forces under General Gomes. Unfortunately, the landing was effected only a few hundred yards from a block-house where a Spanish garrison was posted. Shortly after the landing, the U.S. forces were ambushed and the majority of troops abandoned the beachhead, leaving behind at least 16 wounded comrades, who were taken prisoner by the Spaniards.

Back aboard the U.S.S. Florida, a call for volunteers to rescue the 16 men was made. After several unsuccessful attempts at saving the men had been made by others, Private Wanton, Private Dennis Bell, Private Fitz Lee and Private William H. Thompkins stepped forward and volunteered for the assignment of recovering the prisoners.. Putting ashore in a launch, Wanton and his men surprised the Spanish forces holding the prisoners in a stockade and secured their release. Wanton and his men, together with the freed prisoners, were all able to return safely the ship.

For this deed, Dennis Bell, Private Fitz Lee, Private William H. Thompkins and Private George Henry Wanton were all awarded the Medal of Honor on June 23, 1899.

Wanton was promoted to Sergeant in 1898 and served the remainder of his army career with the 10th Cavalry. Sergeant Wanton retired from the service in 1925. He was invited to visit Washington and act as an Honorary Pall Bearer at the burial of the Unknown Soldier of World War I in the Memorial Amphitheater at the Arlington National Cemetery in 1921.

George Henry Wanton died on November 27, 1940 at Walter Reed Hospital in Washington D.C. He was buried with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington Virginia.

World Wars

World War I

Over 400,000 African-Americans served in uniform during World War I. Most of these men were assigned to stevedore-depot and other laborer units, but approximately 10 percent were assigned to combat units.

Despite segregation and discriminatory assignments, 1,300 African-Americans were commissioned officers. The highest-ranking black officer, and the first African-American to reach the rank of colonel, was Charles Young (section 3, site 1730). Much controversy surrounded the medical retirement of Col. Young, who was the third black graduate of West Point. To protest his forced retirement, he rode his favorite horse from Ohio to Washington, D.C., to prove his stamina and appeal for reinstatement. Many people felt he was retired to prevent his eventual promotion to general officer during wartime expansion.

Col. Young was not reinstated until a few days before the war ended. He died in 1922, while serving as military attache in Liberia. His memorial service was conducted in the Memorial Amphitheater with more than 5,000 people present.

The first African-American combat troops arrived in France in December 1917. The 369th Infantry, known as the Harlem Hellfighters, joined the French 4th Army at the front. The unit stayed in the trenches for 191 days, the longest front-line service of any American regiment. Among the soldiers was 30-year-old Spottswood Poles (section 42, site 2324). Although a combat veteran with five battle stars and the Purple Heart, Poles was often referred to as “the black Ty Cobb.” His claim to fame came in baseball; he was considered the finest player in the Negro leagues in the early 1900s. In 1914, for example, Poles recorded a batting average of .487.

Henry Johnson (section 25, site 64) was also a member of the 369th. He fought in the Argonne Forest and was the first American soldier to earn France’s highest military honor – the Croix de Guerre. On the night of May 14, 1918, Pvt. Johnson and Pvt. Needham Roberts were on sentry duty when a squad of Germans began firing at them. Roberts was severely wounded soon after the firing began. Johnson continued fighting even after taking bullets in the arm, head, side and suffering 21 wounds in hand-to-hand combat. Johnson was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart and the Distinguished Service Cross. On June 2, 2015, President Barack Obama posthumously awarded Johnson the Medal of Honor to Pvt. Johnson for “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty.”

In WWI Despite segregation and discriminatory assignments, 1,300 African-Americans were commissioned officers.

Office of Army National Cemeteries

World War II

When World War II arrived, more than 2.5 million African-Americans registered for the draft. Almost 75 percent of them were assigned to the Army. By September 1944, 8.7 percent of the Army was black. African-Americans were predominately assigned to service or combat-support units, and only a small percentage to combat arms. Within the combat-support units, African-Americans were segregated in quartermaster and transportation units.

By war’s end, members of the segregated 92nd Infantry Division received more than 12,000 decorations and citations, including nearly 1,100 Purple Hearts, 16 Legion of Merit Awards, 95 Silver Stars and two Distinguished Service Crosses. They suffered more than 3,000 casualties. Two black division officers, 1st Lt. John R. Fox and 2nd Lt. Vernon J. Baker (section 59, site 4408), received belated Medals of Honor on January 13, 1997. Fox’s Medal was presented posthumously.

The segregated 761st Tank Battalion fought for 183 continuous days in more than 30 major assaults in the European Theater of Operations. After six nominations, the battalion finally received the Presidential Unit Citation in 1978. The battalion’s white commander, Col. Paul L. Bates, was buried in Arlington National Cemetery, March 1, 1995. Staff Sgt. Ruben Rivers, a black member of the battalion, received a posthumous Medal of Honor January 13, 1997, for his World War II service.

Staff Sgt. Edward A. Carter II, an African-American non-commissioned officer who served with Company D, 56th Armored Infantry Battalion of the 12th Armored Division was awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor January 13, 1997. He was reinterred at Arlington National Cemetery (section 59, site 451) the following day. Other black soldiers who received posthumous Medals of Honor on January 13 were Maj. Charles L. Thomas, Pfc. Willy F. James Jr. and Pvt. George Watson.

On October 25, 1940, Benjamin O. Davis, Sr. (section 2, site 478) became the first African-American general in the regular armed forces. In the course of his 50 years of service, Gen. Davis received the Distinguished Service Medal, the Bronze Star Medal, the French Croix de Guerre with Palm and the grade of commander of the Order of the Star of Africa, Liberian Government.

Almost 150,000 African-Americans served in the Navy during World War II. In 1943, the USS Mason (a destroyer escort) and PC1264 (a submarine chaser) were staffed with all-black crews and all-white officers and petty officers. Within six months, African-American petty officers replaced white petty officers on PC1264. In 1945, the first African-American officer to serve aboard a fighting ship, Ensign Samuel Gravely, was assigned to PC1264. In 1962, then Lt. Cmdr. Samuel Gravely became the first African-American to command a U.S. warship, the USS Falgout. Gravely (section 66, site 7417) would become the first African-American flag officer.

African-Americans did not enter the U.S. Marine Corps until 1942. All 17,000 of them served in segregated units, mainly in service positions. Even though 7,590 were sent overseas, few saw combat.

African-Americans were selected and trained to be pilots at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS (VFW)

On Jan. 16, 1941, when the Army Air Force formed the all-black 99th Pursuit Squadron, the “experimental” Tuskegee Training Program was initiated. African-Americans were selected and trained to be pilots at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. The all-black 332nd Fighter Group was formed soon after and was placed under the command of then Lt. Col. Benjamin O. Davis Jr. (Davis was the first black graduate of the U.S. Military Academy to become a general officer in the regular army. He retired at the rank of lieutenant general). During World War II, African-American women had their first opportunity to serve in significant numbers in the military. Forty of the first 440 officer candidates in the first class of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps were black. Approximately 800 African-American women from the Army, Air Force and the Army Service Forces became the 6888th Central Postal Battalion. Under the command of Maj. Charity Adams, the unit was charged with establishing a postal directory for Europe. Black women also served in the Army Nurse Corps. In 1944, on a “trial basis” African-American women nurses were permitted to treat white American soldiers. The “experiment” was deemed successful.

Tuskegee Airmen

Arlington National Cemetery was established in 1864, and for more than 80 years African-Americans were buried separately from white service men. On July 26, 1948, President Harry S. Truman issued Executive Order 9981, which established, “that there shall be equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion, or national origin.” The new policy was to go into effect “as rapidly as possible, having due regard to the time required to effectuate any necessary changes without impairing efficiency or morale.”

Although it was years before the services effectively integrated, national cemeteries throughout the country adopted the policy immediately and disbanded burial segregation regulation in 1948.

Black Medal of Honor Recipients

VFW Honors African-American Medal of Honor Recipients

VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS (VFW)

More than 3,500 service members have earned the nation’s highest military decoration. But of those, only 92 have been black men, according to the Congressional Medal of Honor Society.

The Medal of Honor (MOH) is an award that dates back to the Civil War. The first African-American service member who earned the prestigious award was Army Sgt. William H. Carney, a man born a slave in 1840 in Norfolk, Va., according to the Department of Defense.

Attached to C Co., 54th Massachusetts Colored Inf. Regt., Carney earned the MOH for his actions on July 18, 1864, during a battle at Fort Wagner on Morris Island, S.C. A battle narrative recalls that his unit’s color guard was shot, and Carney took it upon himself to catch the flag and not let it touch the ground. He is believed to have carried the flag throughout the battle without letting it touch the ground, even when he was wounded. Carney was later presented with the Medal of Honor on May 23, 1900.

Delays in presenting African-Americans their earned Medals of Honor have been common throughout American history. In the early 1990s, the Army worked with Shaw University in Raleigh, N.C., to determine if any racial disparity was present during the process of considering Medals of Honor for black troops.

The investigation determined that seven African-American soldiers should have received the Medal of Honor during World War II. Those seven men are 1st Lt. Vernon J. Baker, Staff Sgt. Edward A. Carter Jr., 1st Lt. John R. Fox, Pfc. Willy F. James Jr., Staff Sgt. Ruben Rivers, Maj. Charles L. Thomas and Pvt. George Watson.

During a ceremony on Jan. 12, 1997, at the White House, all men were awarded the Medal of Honor by President Bill Clinton. Baker was the only living recipient at the time of the ceremony.

As of November 2019, the most recent African-American service member to receive the Medal of Honor was Marine Sgt. Major John L. Canley for his actions during the Battle of Hue in January-February 1968 in the Vietnam War. Canley was presented the award by President Donald Trump during a ceremony on Oct. 17, 2018, at the White House.

Visit vfw.org/magazine to read an article about Canley in the March 2019 issue of VFW magazine.

Content provided courtesy of History.com, Britannica.com and Wikipedia, Tennessean.com Blackpast.com. Channel 11 News, vfw.org. All Rights Reserved.