DAY 15: SCIENCE PT2 – FROM PRACTICAL INGENUITY TO SCIENTIFIC DISCOVERY AND INNOVATION

S.T.E.M. is a term used in today’s education effort that stands for Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics. The following selection of African Americans oriented towards science depicts a snippet of the larger group. From healthcare, computer science, and engineering to ecology, architecture, and aerospace engineering, Black people have moved this country forward in its aim to be a world leader in every phase of life. Here’s the good news. Despite the concerted effort of a select few, African American scientists have profoundly impacted our lives, and there is so much more to come. #LetTheTruthBeTold.

We have chosen to celebrate a select few science pioneers for their determination to change the perception of Black peoples contributions and thus change the landscape and future of our country. Today we honor their genius. We must not let their efforts be forgotten or let others bask in the credit of their achievements. Today we change the narrative. #LET THE TRUTH BE TOLD.

“Prominent Black Scientist cont.”

These trailblazers broke barriers and shattered stereotypes — and went on to conduct research, discover treatments, and provide leadership that improved the health of millions.

IN HONOR OF BLACK HISTORY MONTH READ THE INSPIRING STORIES OF 10 BLACK PIONEERING PHYSICIANS

They fought slavery, prejudice, and injustice — and changed the face of medicine in America. They invented modern blood-banking, served in the highest ranks of the U.S. government, and much more. Read more.

“Historical Black Women Medical Pioneers”

BLACK WOMEN DOCTORS AND NURSES THAT MADE A TREMENDOUS DIFFERENCE

LIKE FATHER LIKE DAUGHTER DR. LOIUS TOMPKINS WRIGHT AND DAUGHTER DR. JANE COOK WRIGHT

Dr. Louis Tomkins Wright

Dr. Jane Cook Wright

Louis Tompkins Wright, medical researcher, war hero and political activist, was born to former slaves in La Grange, Georgia on July 23, 1891. He earned a bachelor’s degree from Atlanta’s Clark University in 1911 and a medical degree from Harvard University Medical School in 1915. Wright’s activism began at Harvard where he missed three weeks of medical school to join NAACP picket lines protesting The Birth of a Nation. Wright returned to his studies, however, and graduated fourth in his class in 1915.

Louis Wright served in France as a physician and Captain in the U.S. Army in World War I. There he successfully implemented life-saving treatments and suffered exposure to poison gas that led to both a Purple Heart and a lifelong respiratory illness. Upon his return to the United States he moved to New York City, New York where in 1919 he became the first African American appointed to the surgical staff at Harlem Hospital. Wright protested the dilapidated conditions of the hospital, raised its patient care standards, improved the professionalism of its staff, and brought the institution to national eminence. He began publication of the scholarly Harlem Hospital Bulletin and established the hospital’s medical library in 1934. During the 1930s Wright authored columns for the NAACP magazine Crisis, where he challenged the contention that biological factors caused African Americans to harbor more syphilis and infectious diseases than the general population. For his work with the NAACP, Wright received the Spingarn Medal in 1940.

Dr. Jane Cooke Wright was a physician and cancer researcher who dedicated her professional career to the advancement of chemotherapy techniques. Wright was born in New York City, New York on November 20, 1919. She was the older of two daughters to parents Louis Tompkins Wright and Corinne (Cooke) Wright. Her familial background included her father, Louis Tompkins Wright, who was one of the first African Americans to earn an M.D. degree from Harvard Medical School, her grandfather, Dr. Ceah Ketcham Wright, born enslaved but who later earned his medical degree from Meharry Medical College, and her step-grandfather, Dr. William Fletcher Penn, who was the first African American to graduate from Yale Medical College.

Jane Wright attended private schools in New York City and in 1942 graduated from Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts with a Bachelor of Arts degree. Three years later Wright graduated from New York Medical College receiving an M.D. degree in 1945.

After internship and residency at Bellevue Hospital, New York between 1945 and 1946, Wright married David D. Jones, Jr., an attorney in 1947. The couple had two daughters, Jane and Allison. Wright’s father, Louis Tompkins Wright, established the Cancer Research Center at Harlem Hospital in New York City in 1947. In 1949 Wright joined her father at the Center and three years later upon his death, succeeded him as the director of what was now the Cancer Research Foundation at Harlem Hospital.

“Cancer Treatment Trailblazer”

Dr. Jane Cook Wright became the medical dean of Harvard medical school.

“Dr. Charles R. Drew”

Dr. Jane Cook Wright became the medical dean of Harvard medical school.

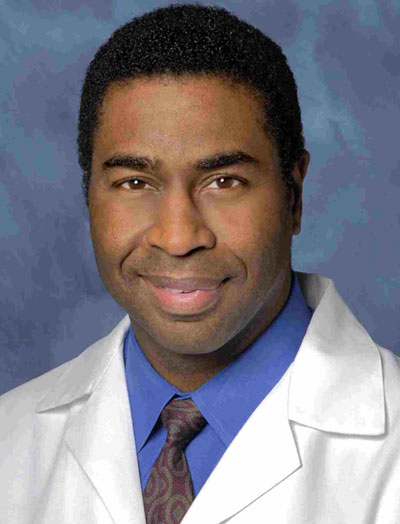

(Neurosurgeon) Dr. Keith L. Black M.D.

(Neurosurgeon) Dr. Alexa Irene Canady M.D.

Keith L. Black (born September 13, 1957) is an American neurosurgeon specializing in the treatment of brain tumors and a prolific campaigner for funding of cancer treatment. He is chairman of the neurosurgery department and director of the Maxine Dunitz Neurosurgical Institute at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, California.

Keith Black was born in Tuskegee, Alabama. His mother, Lillian, was a teacher and his father, Robert, was the principal at a racially segregated elementary school in Auburn Alabama, prohibited by law to integrate the student body, Black’s father instead integrated the faculty, raised standards, and brought more challenging subjects to the school.

Later in his childhood, Black’s parents found new jobs and relocated the family to Shaker Heights Ohio. Black attended Shaker Heights High School. Already interested in medicine, Black was admitted to an apprenticeship program for minority students at Case Western Reserve University, and then became a teenaged lab assistant for Frederick Cross and Richard Jones (inventors of the Cross-Jones artificial heart valve) at St. Luke’s Hospital in Cleveland.

At 17, he won an award in a national science competition for research on the damage done to red blood cells in patients with heart-valve replacements. He attended the University of Michigan in a program that allowed him to earn both his undergraduate degree and his medical degree in 6 years. He received his M. D. degree from the University of Michigan Medical School in 1981.

Alexa Irene Canady, MD, was a pioneer of her time, both for women physicians and African Americans, when she became the first African-American woman neurosurgeon in the United States in 1981.

“The greatest challenge I faced in becoming a neurosurgeon was believing it was possible,” she is famously quoted.

Born in 1950, Canady grew up in Lansing, Michigan, where her father was a dentist and her mother an educator. She graduated from the University of Michigan in 1971 with a degree in zoology, and it was during her undergraduate studies that she attended a summer program in genetics for minority students and fell in love with medicine.

Canady went on to graduate cum laude from the College of Medicine at the University of Michigan. She initially wanted to be an internist but became intrigued by neurosurgery during her first two years of medical school. It was a career path that some advisers discouraged her from pursuing, and she encountered difficulties in obtaining an internship. But she persisted. Eventually, Canady was accepted as a surgical intern at Yale-New Haven Hospital in 1975, breaking another barrier as the first woman and first African American to be enrolled in the program.

Excellence or Performance will transcend artificial barriers created by man”

DR> CHARLE R. DREW

Content provided courtesy of History.com, Britannica.com and Wikipedia.com, Biographies.com, Blackpast.com, notablebiographies.com, aamc.org. and medicine.iu.edu. All Rights Reserved.